The 0Maths blogThe Research that Makes 0maths Different

A 2022 UCL study found that only 1 of the top 25 maths apps on the Apple store and Play stores was effective. At 0maths, we began with the goal of making the most effective maths platform possible. We've used findings from Educational Psychology as the basis for every aspect of its design:

Gamification

Gamification in maths platforms is often interpreted as a narrative (eg slay the dragon / race your friend / dog with your numeracy skills).

Outside of maths platforms, gamification is much broader and more sophisticated. It is intrinsic to everything from banking apps to the dark design of gambling apps and social media. It simply means utilizing design that taps into the brain's reward pathways. This is the approach we've adopted.

Gamification on 0maths is not:

-

An interactively animated background (ie your avatar's progress is related to your maths progress).

Unsurprisingly, parallel tasks and animated backgrounds are proven to be distracting. Maths requires cognitive capacity and reducing extraneous cognitive load maximises student potential.

-

We don't offer peer-to peer competition either. Aside from reducing inclusivity and cooperation in the classroom, peer to peer maths competition seems to benefit only the top students, largely at the expense of the bottom half of the class, where it exacerbates maths anxiety, reduces attention levels, and negatively impacts progress:

-

From duels to classroom competition: Social competition and learning in educational videogames within different group sizes [Nebel, Schneider, Rey, 2016]

-

The Effects of Peer Competition-Induced Anxiety on Massive Open Online Course Learning [Liu, 2024]

-

For so many maths apps, working very quickly against a computer or against an opponent seems to be the definition of success. This can be detrimental to learners relationship with maths in several ways:

- Increased maths anxiety - which can easily snowball, causing increasing disengagement [Geist, 2010].

- Reduced accuracy [Roeper 2007].

- Negative messaging: children learn that reflexive answers are 'better' than answers which have been thought about.

- Time pressure reinforces familiar strategies rather than trying something unfamiliar and more appropriate.

[Suárez-Pellicioni, Núñez-Peña & Colomé, 2015 ]

- Mistakes can't be learned from.

-

Rewarding performance rather than learning reinforces a performance mindset, as opposed to a growth mindset:

How growth mindset influences mathematics achievements: A study of Chinese middle school students [Dong, Jia, Fey 2023]

-

Effects of Math Anxiety and Perfectionism on Timed versus Untimed Math Testing in Mathematically Gifted Sixth Graders [Roeper 2007]

-

So how does 0maths gamify maths?

To target dopamine, there are rewards for each question and each step of a question; these rewards are designed to not disrupt the flow. Learners achieve the satisfaction of completing question types and topics, ascending difficulty levels and winning awards for progress. It is apparent to them that they are making progress. A clear maths problem at the right level brings the same type of satisfaction as solving a puzzle.

-

We do use timings as a success indicator on 0maths, but we do so very carefully.

- Learners acheieving correct answers win a silver award, or a gold award if they did it within the time target. Time targets are mostly generous, except for multiplication facts (tables) and number bonds where there are rewards for automaticity. A silver award is not failure. Taking a long time is not a catastrophe - it shows students that they are making good progress.

- Bridging topics (e.g. the 50 or so different learn-a-table activities) have generous time limits so all students can win a majority of gold awards.

- Once the foundations are solid and the facts are comitted to memory, timed activities are there for practice.

Motivation

The rewards on 0maths are crafted to be intrinsic and informational (ie emphasising what they have done well). This contrasts with some other platforms where rewards are extrinsic and controlling. Studies show that such extrinsic controlling rewards actually reduce intrinsic motivation [Ledford, Fang and Gerhart, 2013]. Learners may enjoy time on such platforms, but they enjoy maths less as a result.

Mostly not multiple choice

Multiple choice is the most common format in primary maths platforms. It is one tool in the box. We use it only where it's the right tool - about 1% of question types. Besides being "hackable" (ie odd / even) and obstructing flow, multiple-choice testing can inadvertently create false knowledge. Exposure to incorrect answer choices (lures) during multiple-choice tests can cause students to later recall or believe these incorrect options are true, a phenomenon known as the "negative suggestion effect".

[Jonge, 2023]

Question format

- Our never wrong, but perhaps not-yet-right answers approach has the backing of several studies:

-

We learn by getting things right, not by getting them wrong. [Eskreis-Winkler and Ayelet Fishbach, 2020]

-

No post-error slowing (PES). [Naaman & Goldfarb, 2021]]

-

Low-confidence answers are reinforced. [Fabio, Huessler, Johnson & Marsh 2010]

-

Errors increase cognitive load. [Suárez-Pellicioni, Núñez-Peña & Colomé, 2015 ]. Taking errors off the table reduces cognitive load.

-

Reduce anxiety levels and free-up working memory.[Dowker, Sarkar & Looi, 2016]

The effect of instant marking

Anyone who tries training a pet will know there is a massive difference between instant feedback, and feedback a few seconds later (ie after a question has been submitted as opposed to while it is active in the student's mind). Humans are the same. Marking answers instantly leads to better retention, especially for students with low prior knowledge: Effect of Immediate Feedback on Math Achievement at the High School Level [Razzaq, Ostrow Heffernan, 2020]

Adrenaline vs dopamine

On many maths platforms, adrenaline provides the addictive element by racing against peers or some sort of ticking bomb.

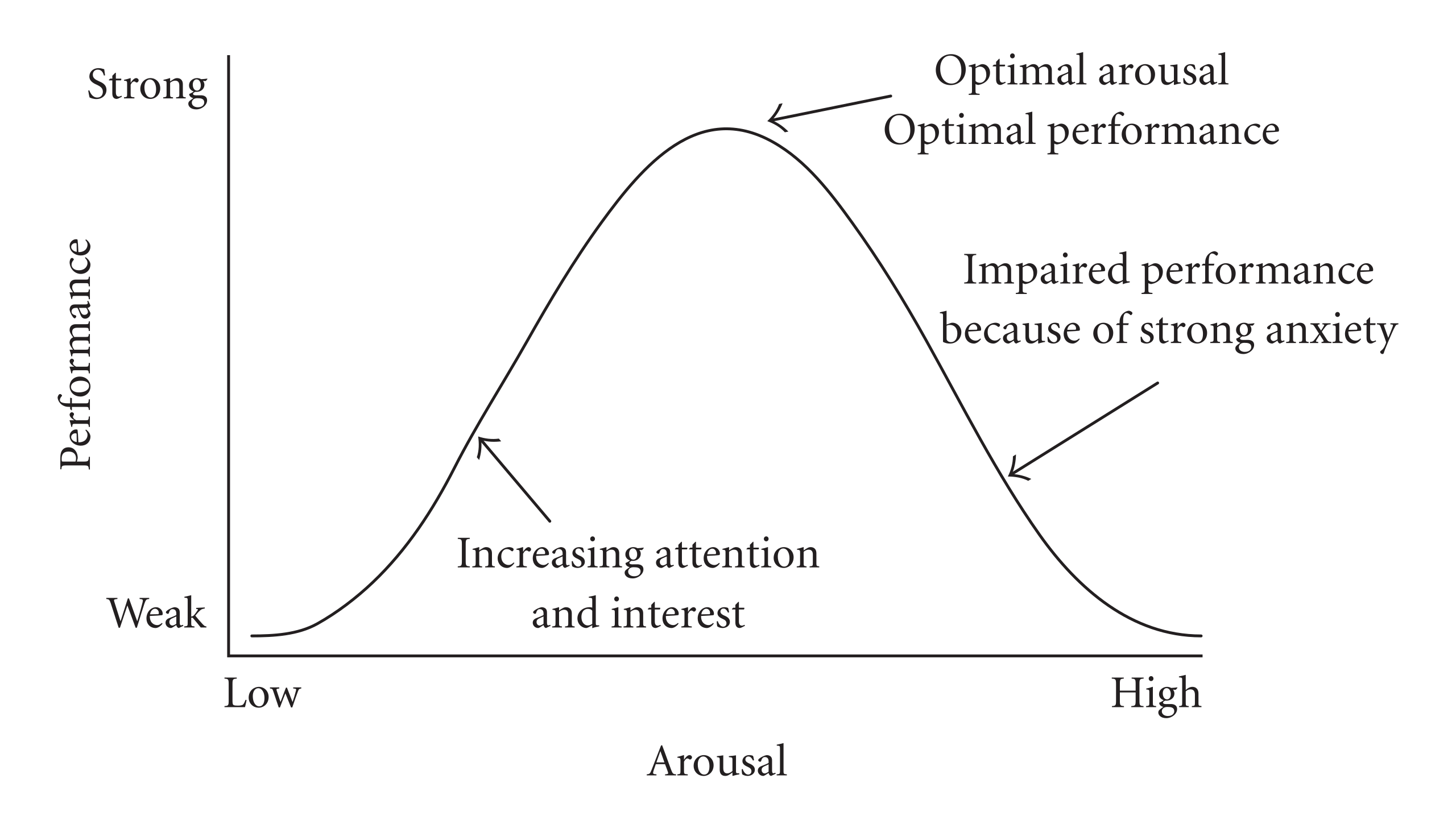

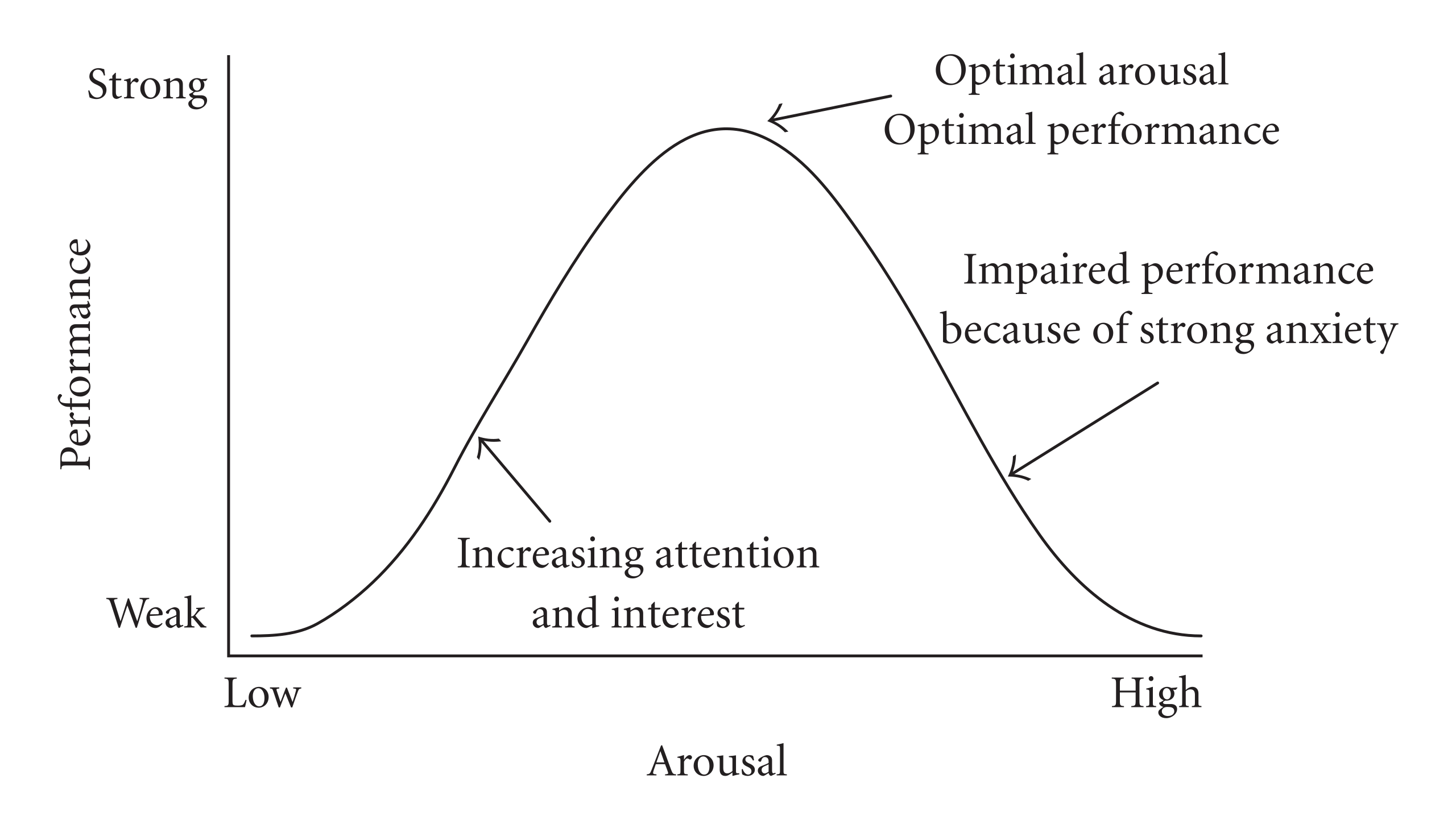

If you search Google images for "stress performance" you get a curve known as the Yerkes-Dodson curve.

This is a misinterpretation of their results. Their actual (1906) paper "The Relation of Strength of Stimulus to Rapidity of Habit-Formation" looks at the effect of electric shocks on which route Japanese dancing mice would take through a maze. There was a simple discernment task (white box vs black box) and a difficult discernment task (same black and white boxes, misleading lighting). Notably, the mice did not require working memory (which is inhibited by adrenaline) and had no other motivation (ie no 'cheese' for getting it right). To interpret their research as the popular "Yerkes-Dodson curve" you have to assume that trials to completion corrleates to cognitive capacity and that the strength of an electric shock correlates to arousal. A simpler explanation is that in the solitary data point from which the entire left hand side of the curve is drawn (ie where low arousal = low performance), the mice weren't too bothered about the electric shock.

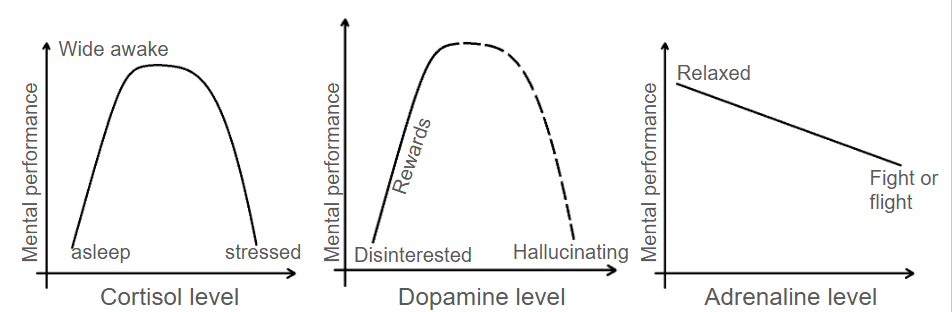

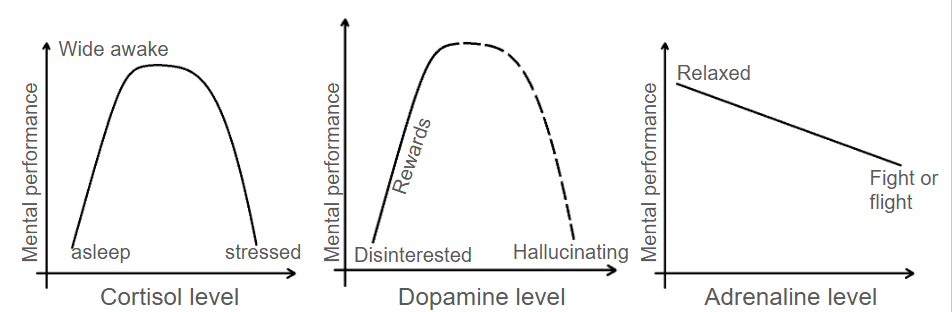

There are many modern studies that have added a bit of nuance here. We can break down stress into 3 physiological responses:

- The major effect of cortisol is our daily rhythm - reducing brain activity at bed time and being alert during the day. Added stress, such as anxiety, only disrupts this cycle, shifting it to the right, making thoughts disrupt sleep.

- Dopamine makes us feel good and improves cognition, helping us stay in the zone. The right hand side of this curve, where cognition begins to decline and eventually become hallucination is not normally accessible, except through schizophrenia or drug use. Cortisol was injected in the experiment.

- The effect of adrenaline is straightforward. It is directly and proportionately negative. The more adrenaline, the worse cognitive performance.

Back to maths:

By eschewing time based failure, peer-to peer competition, and even wrong answers, we decrease adrenaline levels (which are in any case elevated for many students when doing maths, and have a bigger impact on autistic learners). Instead, because answers on 0maths are never wrong, and multi stage problems are often broken down with marked workings, the constant stream of correct answers triggers dopamine* release.

* dopamine levels can also be increased through exposure to sunlight, getting sufficient sleep, healthy diet (especially protein: turkey, eggs, beef, legumes, and dairy) and exercise. That's out of our remit but it would be remiss to not mention the broader picture.

The colour scheme

- Although children prefer bright colours, they find them distracting, so the look of 0maths is low key. Compared to other primary school resources 0Maths may look a little more 'adult' - unsurprisingly adults also find bright colours distracting. Source:

Disruptive Effects of Colorful vs. Non-colorful Play Area on Structured Play

Where we use bright colours they are at the focal point of the question.

- Being in green spaces (ie on grass or in woodland) has been shown to be calming and is especially beneficial to children suffering with ADD and ADHD. There's no evidence that a green screen can produce the same effect. However, green is culturally perceived a calming colour and that's the message we want to convey - ie 0maths is a place of reduced anxiety, so we've gone green but there's no science behind it.

- It is possible to mute the colours further for ADD / ADHD students (in the settings).

Typing versus handwriting

If appropriately equipped (ie using an ipad and an apple pen) it is possible to use 0maths with handwritten, as opposed to typed, answers so we can happily sit on the fence for this issue. It makes for an interesting discussion though, as the popular interpretation of the research is not at all related to what the research tested.

Several well publicisized studies (i.e. Handwriting but not typewriting leads to widespread brain connectivity: a high-density EEG study with implications for the classroom, Van der Weel, Van der Meer, 2023) have demonstrated increased and more interconnected brain activity when writing by hand as opposed to typing. This in itself is not especially surprising; handwriting requires more muscles, moving more intricately, in a more coordinated manner than typing. It would be surprising if handwriting did not induce more brain activity.

However, such studies have often been interpreted to mean writing things by hand leads to better retention, but it's important to note that they did not test for this. Their own wording, not directly supported by their research, is qualified ("Thus, the ongoing substitution of handwriting by typewriting in almost every educational setting may seem somewhat misguided as it could affect the learning process in a negative way"). I'll say it again: they did not test for this conclusion and provided no direct evidence for it.

An alternative interpretation of the same study (not presented by its authors) is that cognitive load increases more with handwriting than with typing. This is directly supported by the conclusion of another study that handwriting deteriorates with cognitive load - ie handwriting utilises cognitive capacity. (A legibility scale for early primary handwriting: Authentic task and cognitive load influences [Staats, Oakley and Marais, 2019] ). As a large part of the task of teaching maths is to reduce cognitive load as much as possible, this would seem to imply that typing would be better than handwriting.

Straying from maths, there are several studies looking at college performance when typing notes versus handwriting and they all seem to have different conclusions - here's a good discussion on the subject. The study alluded to in the above article looked at student exam results and how they took notes (ie typed or by hand). This got much more emphatic results (in favour of handwriting) than previous studies. However, the key difference is likely to be the students' ability to add diagrams and mind maps into their notes rather than the mechanism for forming words.

The optimal solution may not be the same for all students.

Nurturing maths awesomeness

Nurturing maths awesomeness